After a few nights out at sea, Captain Hunter steered HMS Sirius toward Sydney Bay in close to Phillip Island on the morning of 19 March at 9am with a small wind form the south-east. HM Supply had already arrived and the flag signal was flying showing it was suitable for long boats to land without any danger from the surf so HMS Sirius sailed closer to shore and Nepean Island.

At the stroke of midday 19 March 1790, HMS Sirius struck the Sydney Bay reef. There are numerous first hands accounts of the shipwreck event and activities of following days, some with slight contradictions. Captain John Hunter account in An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island 1787 – 1792 does not go into great depth compared to A Voyage to New South Wales, The Journal of Lieutenant William Bradley, RN of HMS Sirius 1786 – 1792 and seaman’s Jacob Nagle his Book A.D. One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Nine May 19th. Canton. Stark County Ohio, 1775-1802 and other reports.

Captain Hunter was anxious to take advantage of the signal and the suitable conditions for land ing the cargo of long awaited provisions onto Norfolk Island. By 11am HMS Sirius had started loading sending boats to be sent ashore with baggage and provisions, there was a slight breeze off shore, and many of the seaman were actually fishing off the deck with a hook and line, catching grouper and not thinking on any possible danger surrounding them.

The first long boat was sent ashore, whilst loading the next boat Lieutenant Ball of HM Supply hailed from the ship which was situated off HMS Sirius lee bow (left front) waving his hat towards the reef of sunken rocks which lay off the west point of Sydney Bay. The next long boat which was only half loaded was sent to shore. On that Captain Hunter observing that the ship settled fast to leeward, and made sail, and immediately hauled on board the fore and main tacks, the HM Supply had also made sail, and was to leeward of HMS Sirius.

In a short space of time, there was a sudden change of tide and swell, along with a wind shift to the south, HMS Sirius after releasing the anchor tried to sail (tack) towards Nepean Island and the East point of Sydney Bay to distance the ship from the danger of the reef and as the only chance of saving the ship, however the surf swell and wind were too strong and had a hold on the ship, the next wave dumped HMS Sirius onto the reef. Captain Hunter wrote:

… as we drew near, I plainly perceived that we settled so fast to leeward that we should not be able to weather it: so, after standing as near as was safe, we put the ship in stays; she came up almost head to wind, but the wind just at that critical moment baffled her, and she fell off again: nothing could now be done, but to wear her round in as little room as possible, which was done, and the wind hauled upon the other tack, with every sail set as before; but still perceiving that the ship settled into the bay, and that she shoaled the water, some hands were placed by one of the bower anchors, in five fathoms water; the helm was again put down, and she had now some additional after-sail, which I had no doubt would ensure her coming about she came up almost head to wind and there hung some time but her sails being all aback, had fresh stern way, the anchor was therefore cut away and all halyards, sheets and tacks let go, but before the cable could be brought to check her she struck upon a reef of coral rocks which lie parallel to the shore and in a few strokes was bulged. When the carpenter reported to me that the water flowed fast into the hold, I ordered that the masts be cut away which was immediately done. There was some chance, when the ship was lightened of this weight, that by the surges of the sea which were very heavy, she might be thrown so far up the reef as to afford some prospect of saving the lives of those on board if she should prove strong enough to bear the shocks she received from every sea. [1]

HMS Sirius struck the reef again with the next wave, by this time there was over four feet to seven feet, (accounts do vary) and flowing in fast into the hull of the bulging ship, now located even closer to shore before the swell broke once more against the ship, the crew were able get one boat alongside, and send safely ashore Captain Cook’s timepiece and two marines wives, pregnant Maria Nash and Margaret Gilbourne. Captain Hunter then ordered the mast to be cut away by cutting the lanyards and rigging. An anchor was immediately let go on her first striking, and in less than ten minutes every mast was over her side and the ship an entire wreck.[2]

An anchor was let go, which prevented the ship from coming broadside to on the reef. Captain John Hunter also gave orders to open the aft hatch way and save all the liquor that could be got at to prevent the seamen from getting drunk. The crew began to secure their clothing in their chests and they were lowered overboard by rope hoping they would float to the shore. But the current setting to the west took them out to sea, and all was lost. The lanyards of the starboard rigging being from the cut masts and sails did eventually drift to shore along with loose clothing that was thrown overboard.[3]

Midshipman of HMS Sirius John Harris wrote: She (the ship) came round, and having sternway before she could fill went on the reef in great surf. The mast was instantly cut away, and in ten minutes the ship was a perfect wreck. All the bread and such of the dry provisions that was at hand, with the timekeeper, were sent away in the boats, when the surf rising and the wreck being alongside no more boats could come to us.[4]

It is not known if Captain Cook’s timepiece was sent ashore before or after the masts was cut down at the time of the wreck.

HMS Sirius by way of the heavy surf which broke over her being thrown again on to the reef, it was now impossible to hold any idea getting the ship afloat off the reef. Seeing HMS Sirius in trouble on the Sydney Bay reef Lieutenant Ball of HM Supply came as near the Ship in his boat as he could to ask if the Supply could be of any use. Captain Hunter told him No! …. that the Sirius was gone and desired him to take care of the HM Supply. On shore at the time of the wreck, Ralph Clark watched in horror from the shoreline, he later wrote in his journal:

…. gracious god what will become of us all … God that we will be able to save some if not all but why do I flatter myself with such hopes … there is at present no prospect of it except that of starving, what will become of the people that are on board for no boat can go alongside for the sea and here am I who has nothing more than what I stand in and not the smallest hope of my getting anything out of the ship for everybody expects that she will go to pieces when the tide comes in.[5]

All hands on board brought up as much as possible provisions, supplies, chest to the gun deck in case an opportunity was found to float these items ashore. Upon deciding to quit the ship, the crew were able to get a hawser from the ship to the shoreline, with a wooden heart upon it for a traveller by means of a cask, floating a rope over the reef and through the surf, which those on shore hauled the end of the hawser and secured around a pine tree, with the other end being on board the ship was hove taut. The ship’s company was hauled ashore though the surf to the reef, from which they crossed to the shore in a small boat positioned inside the reef.[6]

[1] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island 1787 – 1792.

[2] Jacob Nagle, Jacob Nagle his Book A.D. One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Nine May 19th. Canton. Stark County Ohio, 1775-1802; Newtown Fowell letter to his father, 31 July 1790 Batavia, HRA, Series 1, Volume 1, pp. 373 – 386.

[3] Jacob Nagle, Jacob Nagle his Book A.D. One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Nine May 19th. Canton. Stark County Ohio, 1775-1802.

[4] Jacob Nagle, Jacob Nagle his Book A.D. One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Nine May 19th. Canton. Stark County Ohio, 1775-1802;Banks Papers, HRNSW, Vol. 1, Part 2, p. 345 – 342.

[5] Ralph Clark, The Journal and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787-1792.

[6] William Bradley, A Voyage to New South Wales, The Journal of Lieutenant William Bradley, RN of HMS Sirius 1786 – 1792;Ralph Clark, The Journal and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787-1792.

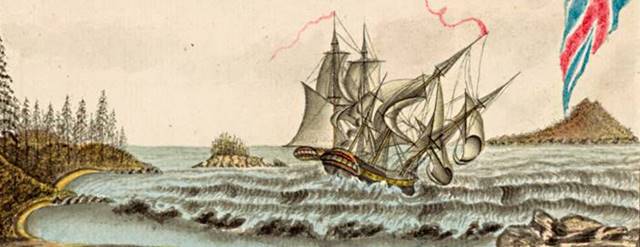

Image: The melancholy loss of HMS Sirius off Norfolk Island, showing HM Supply in the background, 19 March 1790, George Raper. National Library of Australia.